The Third Republic

Glasnost to present

Tour Armenia

GLASNOST AND ARTSAKH 3RD REPUBLIC 1996-2002 ARMENIA NOW

Glasnost and Artsakh

At first enthusiastically supporting Gorbachev’s doctrines of Glasnost (openness) and Perestroika (restructuring), Soviet Armenians became disillusioned as the economy continued to stagnate and Russians began to discriminate against Armenians for their wealth and influence. Two events in 1988 precipitated Armenia’s separation from the Soviet Empire.

In 1988, a movement of support began over the struggle of Nagorno Karabakh Armenians to exercise their right to self-determination. Nagorno Karabakh (Artsakh) is a part of Historic Armenia, and was an autonomous region in the Republic of Azerbaijan. The separation of Nagorno Karabakh from Armenia--like the separation of Nakhichevan (also predominantly populated by Armenians) was made by decision of Stalin in 1923. There had always been tension between Armenia and Azerbaijan (of Seljuk-Turkish lineage), and the independence movement in Nagorno Karabakh increased in fervor especially after the 1988-89 massacre of Armenians in Sumgait, just north of the Azerbaijan capital of Baku. Armenians were seeing a replay of the Turkish genocide with the apparent acquiescence of the Soviet authorities. During 1988 the support for Nagorno Karabakh movement developed into an independence for all Armenians movement, as increasing numbers of people marched through the capital and in other cities.

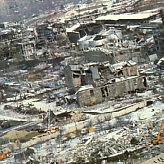

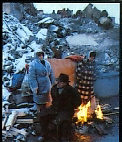

In the same year Armenia was rocked by severe earthquakes (the epicenter was near Spitak) that killed more than 25,000 of people in a 100 kilometer band across the North of the Republic. It is estimated that up to 15,000 people died in the first tremor, as poorly constructed concrete buildings (the hallmarks of the Brezhnev era) collapsed on families, factories and schools. At first refusing to admit to the outside world that anything had happened, the Soviet government then refused Western offers of help. Constant bungling by the Soviet authorities to help survivors and bring in aid led to bitter criticism of the central government. The Soviets finally made an appeal for aid, and for the first time in decades the Soviet borders were opened to caravans of medicine, construction material and aid workers from the West.

Exasperating this effort was the beginning of an energy blockade by Azerbaijan, which refused to help Armenia, further frustrated by a land and air blockade against Armenia by Turkey, especially Turkey's blockade against humanitarian aid. Turkey saw an opportunity to reinvigorate its decades old dream to expand its influence in Central Asia and form a pan-Turkish sphere of influence to counterbalance the Iranian-Persian sphere in the same area. Tensions rose until Azerbaijan attacked both Nagorno Karabakh and Armenia in 1990, killing hundred of Armenians in Baku and Kirovabad, including 300 Armenians in Sumgait, most having their throats slit by Azeri Nationalists. This began an undeclared war between the two states.

3rd Republic

This issue has dominated Armenia's political arena since the first democratic election held in Armenia during the Soviet era. In 1990, the Armenian National Movement won a majority of seats in the parliament and formed a government. On September 21, 1991, the population overwhelmingly voted in favor of independence in a national referendum, creating the second independent Armenian republic. On October 16, 1991, after constitutional changes mandated the direct election of the president, Levon Ter-Petrossian, a leader in the National Movement, was elected to this post from among many other presidential candidates.

Between 1991 and 1996, the republic continued its support of the Nagorno Karabakh conflict, and felt horrendous effects from the blockade by Turkey and Azerbaijan. The cut off of gas and oil from Azerbaijan effectively collapsed the economy, as did the end of economic ties with other Soviet Republics, on which Armenia depended for raw materials. The centralized Soviet economy had the common practice of separating the source of supply from its final processing point, thereby increasing dependence of separate regions on Moscow. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the entire structure disintegrated, suppliers were unable to reach manufacturers, and the worker-heavy industries were no longer able to process or sell products. The primary rail link between Armenia and Russia lies in Azeri territory, which worsened the situation. In addition, Armenia’s northern neighbor Georgia went through tumultuous changes of its own, experiencing a civil war and general breakdown of law and order.

Without electricity and raw materials, Armenia suffered through three successive winters without heat or electricity, and a one-year loss of 70% economic activity. The government was unable to effectively address these problems, except to immediately begin a privatization program and to begin ties with both the West and the new republic of Russia. Huge amounts of American and Western aid poured into the country, and the "Freedom of Aid" law passed in Congress isolated the Azeri’s, who--despite huge oil fields, faced the same collapse of their economy as elsewhere.

The Armenians in Nagorno Karabakh succeeded in repelling Azeri advances in 1993 and 1994, cutting off Azeri territory nearest Armenia and setting up a buffer zone consisting of about 23% of previously Azeri territory. A truce was signed in 1995, and has thus far held, with Nagorno Karabakh declaring itself a republic. Both Armenia and Azerbaijan have agreed to settle the dispute through negotiations, though Azerbaijan demands the return of Nagorno Karabakh to its territory.

In 1995 a new Constitution was passed by referendum, and Ter-Petrossian won reelection in September of 1996, in a controversial election contested by the opposition and some election observers. The population was divided in its support, feeling on hand that unified support against Turkish aggression had to be maintained, while on the other hand watching government officials and a new class of entrepreneurs achieve wealth at an astonishing rate. When Ter-Petrossian was declared the winner in districts where voting fraud has been reported, opposition marches became more virulent, with protesters storming Parliament and beating the Speaker of the House. The government called out the army, and skirmishes ensued until soldiers fired above the crowds' head, forcing them away. Fortunately no one was wounded. Soldiers secured the streets and most important buildings in Yerevan long after it grew quiet, and specially televised parliament meetings condemning the opposition had the opposite effect of convincing people that the government had stolen the election, and had much to hide. In fact, the government did win the election, if by the slimmest of margins. Ter Petrossian promised to institute reforms in the government, but cabinet shuffles were repeatedly horizontal in design, causing increasing cynicism in the population.

1996-2005

1996 was also marked by the development of the Caspian Oil Field by a consortium of British and French Oil companies (sound familiar? If not, see the Great Game, above), joined by American Oil concerns, has hardened Azerbaijani demands in resolving the conflict with Armenia. Azerbaijani officials have openly stated that they will dedicate income from the oil wealth towards beefing up their army for renewed fighting. The Great Powers counter with "over our oil rich dead bodies", and are trying to force a negotiated settlement, with the eventual return of Nagorno Karabakh as an autonomous country within Azerbaijan. Sounds like Article 16 of the 1878 Berlin treaty, doesn't it? It appears the stalemate will continue. None of the powers involved in the oil pipeline development (including Russia and Turkey) want a resumption of conflict, which will immediately jeopardize their profits, and the billions in investments they are making to pump the oil. In the meantime, Armenia's economy moved ahead of others in the Caucasus States, continuing to hold the fastest growing GDP in the former Soviet Union.

Rampant corruption (annoying to outsiders facing petty bribe demands by police and highway patrols, but devastating to the local population struggling to live on a monthly average salary of less then $35) sent mixed signals to the outside world: at once courageous and willing to make huge sacrifices in the face of attacks by Azerbaijan, did the country really want to join the world stage as a normal country. No less a problem then in any other Eastern block or Soviet country, the corruption nevertheless told investors and donors that the people on top cared very little for the people they were elected or appointed to serve. It is an ingrained reflex to all Soviet citizens to distrust the powers that be, and to expect lies and deceit. This led to extreme pessimism in the population, and a drop in the number of persons voting. By the time the second elections were held in 1998, there was a 25% drop in attendees.

And a huge surge in emigration. Estimates are notoriously suspect, but UN counts of passengers leaving the country between 1994-1999 do estimate that at least 750,000 persons left Armenia in that time. That is only by plane. There may be as many who left by land routes. Some say from the 1990 census figure of approximately 3.5 million, the actual population of Armenia now sits around 2 million, perhaps less. A current census taken in 2001-2002 should shed better light on just how many people remain.

Ter Petrossian attempted to force the issue of Karabakh by declaring his willingness to compromise in order to achieve a lasting agreement. Feeling the only way to achieve peace was to take the initiative, he declared his willingness to relinquish much of the buffer zone around the enclave in exchange for a peace treaty. The reaction by nationalists and the opposition was quick. Accusing the president of betraying the Karabakh cause, the leaders of parliament began to take steps to remove him from office. In the frenzy that followed, much of what Ter Petrossian actually said was lost, and the exact same proposals are being considered today. But the population was unable to support him, having made too many sacrifices in the past years and facing so much obvious corruption and graft from the political elite. Ter Petrossian--perhaps the most intelligent man in the country--represented to the vast majority not the hope of a new vision, but rather the desperation of their lives. Unable to muster the support he needed in parliament, Ter Petrossian was forced to resign in 1998. The following election in March 1998 chose Robert Kocharian, the president of Karabakh, who seemed the hawk the country wanted. Vazgen Sarkisian, heretofore leader of the army, became Prime Minister.

Kocharian faced the same governmental intransigence and corruption as his predecessor, and the same accusations of graft or at least benefiting from association with power brokers and the new Mafia. None has been proved by independent sources, but the effect was the same. The country entered a long period of cynicism and loss of faith it has yet to recover from.

In 1997-1999, complaints over corruption grew louder, particularly toward the army and its graft. Stories of conscripts buying their way out of service, and of a string of mysterious deaths in the army, alleged to have been done by officers and fellow soldiers rocked the country in 1997-1999. With a sudden drop in economic productivity in 1997 and a rise of inflation to 23% that same year, protests and political rest grew, even while the typical Armenian either left the country for better lives, or simple struggled to get by.

In 1998, tensions rose, with hotly contested parliamentary elections in May, local elections in July that had been marred by violence among supporters of the former prime minister, and a series of direct meetings between Armenian president Robert Kocharian and Azerbaijani president Heydar Aliyev to discuss resolution of the Nargorno Karabakh conflict. President Kocharian had announced earlier in the month that he was optimistic about the prospect of a settlement of the eleven-year-old conflict. The elections in 1998 for parliament were declared fair by international observers even though there was a certain drop in the number of voters and the populace cynically announced the new prime minister Vazgen Sarkisian's election a "coronation" for the man who really pulled the strings of power in Armenia.

That same year a new patriarch (Catholicos) was elected, following the death of Garegin I, who died of cancer in June, 1999, aged 66. Garegin I, who was also head of the Cilician arm of the Apostolic Church, had been elected with hopes of settling a centuries old dispute between the two churches. He was unable to achieve this in his short 4 year tenure. His predecessor, Vazgen I, who ruled from 1955 until his death in Aug. 18, 1994, led the church for almost 40 years, and was greatly loved by Armenians in and out of Armenia, for his independence against Soviet Authorities and ability to revive the church in Armenia.

On October 27, 1999, just as the newly elected Garegin II was delivering his acceptance remarks in Echmiadzin, word arrived that five gunmen had taken the Parliament, wounded the Prime Minister and were holding Parliamentarians hostage. Soon it was learned that both the Prime Minister and the Speaker of Parliament — the two men who jointly dominated the Unity Party which won control of Parliament last year — were dead, as were several other senior officials. By the next day the Army was demanding the resignation of key security ministers, and the country seemed to be on the verge of chaos. The enthronement of the new Catholicos was postponed, and President Robert Kocharian sought to bring the various political parties together in show of national unity (though there were critics who saw Kocharian as potentially gaining strength from the deaths of his political rivals).

The five men who opened fire on the Armenian Parliament were described in the press as "sick " or worse, men who did not have a clear set of demands, other than hatred for Prime Minister Vazgen Sarkissian. Though their leader, Nairi Hunanian, had a past affiliation with the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutiun) Party (Dashnaks for short), dashnaks countered that they had been expelled in the early 1990s.

Reaction on the street was sharply divided between those shocked and grieved over the murders, and those who felt that they had received their just desserts for a decade of corruption and abuse. Few believed Armenia had enjoyed any real democracy since its independence, that the attack and death of Sarkisian and Demirchian were merely symptoms of the general decay of the country's well being and soul. While other alleged perpetrators were falsely arrested and some tortured, the country sank deeper into itself and into reactionary measures, ignoring dialogue about the causes. Journalists who attempted to reveal corruption or investigate the tragedy were arrested, held without charge, and a few tortured before finally being released under international pressure. Sadly, the Diaspora, best equipped to confront the issues behind the situation, divided as deeply into blame and counter blame, or wrapped themselves in patriotic jingoism that further clouded the issue. In the end, few if any know just what triggered such a violent action.

Also in 1998, a 15 year monopoly agreement was awarded to the Greek Telecom OTE to operate Armentel, the national phone company. The agreement permitted exclusive monopoly on all telecommunications, including "those not yet invented", and was decried by international organizations and governments as a sham. The local effect was a stifling of competition and a sharp rise in the cost of communications at all levels. Calls to the USA average $2.40/minute, while calls from the US to Armenia using the same lines can cost only 16 cents a minute. Armenia was told it would not be permitted into the WTO (World Trade Organization) until it could break the monopoly. Over the past 5 years Armentel's grip on telecommunications and the Internet has been gradually broken by the constitutional court, but government members are widely seen as earning cash form the venture and actively working to prop up the monopoly. Officially the monopoly ends in 2003, 10 years ahead of time, by order of the court.

On Thursday, November 4, 1999 Garegin II was finally installed as the 132nd patriarch of the Armenian Apostolic church, the Catholicos of all Armenians.

An opposition headed by elements of the former Armenian National Movement government attempted unsuccessfully to force Kocharian to resign. Kocharian was successful in riding out the unrest. The prime minister's brother, Aras Sarkisian, was appointed to succeed him, but in May 2000 President Kocharian replaced Sarkisian, a political rival, with a new prime minister, Andranik Markarian. Continued progress with Karabakh began in April 2001, when Azerbaijani president Heidar Aliev and Armenian president Robert Kocharian met with American, French, and Russian negotiators, and began to hammer out the details regarding the future of the enclave.

In 2002, a new scandal erupted after the trial for the 24 September 2001 killing in a Yerevan cafe of Georgian-born Armenian Poghos Poghosian by Presidential bodyguard. The guards detained Poghosian in the toilets of the Poplovak (Sail) Cafe and allegedly beat him to death. Kocharian was at the cafe with Charles Aznavour at the time. Human Rights, the international human rights watchdog suggested that witnesses are being intimidated to deter them from offering evidence that Kocharian's bodyguards deliberately beat Poghosian to death.

In February of 2002, the court handed down a two-year suspended prison sentence handed down to Aghamal Harutiunian, one member of President Robert Kocharian's bodyguard, for the manslaughter. The effect on the population was electrifying and for the first time in his tenure, there was doubt as to the president's chances for survival in the next election. What was universally called a sham in the justice system has come to symbolize all that has gone wrong with the country, and the opposition -- known more for its infighting then ability to present a real alternative--looks poised to make real gains. But few believe that the next elections would be fair or representative. This proved true in 2004 when by-elections were seen to be rife with ballot stuffing, intimidation and fraud by international election monitors.

The following period showed both progress economically and a growing separation of the haves and have-not's, with the government elite, lucky entrepreneurs and a widely believed network of Mafia reaping larger shares of the pie. There was wide-spread pessimism that the government or economic leaders can effect any honest practices in their affairs, and few believe the agencies working to develop the country can create any real good. This cynicism continues, with fewer individuals voting in the 2003 elections, which re-elected Kocharian in what is widely believed to have been another unfair election.

The years 2003-2005 saw both an expansion of the economy fed by remittances from Armenian's living abroad (more than $250 million a month) and a widening chasm between the haves and have-nots. Corruption by the government (widely believed on the streets to have been led by the president himself and his closest advisors) is felt to have stifled real growth, with very few earning wealth from the control of vital resources. Strategic resources were either sold to Russian interests in exchange for debt forgiveness (including the primary means of generating electricity) or monopolized by the heads of government ministries.

Others blame money laundering for much of the supposed growth, a construction boom in Yerevan feeding the suspicion. Historic sections of the city were destroyed to make way for concrete behemoths supposing to be sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Many sat empty after construction. Whatever the reasons, job creation was low, despite IMF and World Bank praise for macro-economic growth. Based on remittances from abroad, real economic activity was restricted to tiny businesses and a concentration of Armenia's remaining population and wealth into Yerevan. The capital city has experienced a sort of growth spurt in its center, with buildings and new shops springing up, but jobs and income have not radiated into the regions, or even the suburbs of Yerevan. Villages and rural areas were depopulated as people were drawn to the city in search of work, leaving deserted homes in the regions.

The truce with Azerbaijan dragged on with no real end in sight, neither government able to bid for peace. International mediation continued, while Kocharian and his friends in government found convenience in ragging negotiations out.

In November of 2005, new elections were held to ratify a new constitution, which was supposed to limit presidential powers and bring Armenia more into line with that of the European Union. Widely supported by Europe and the USA, the constitution was nevertheless harshly criticized by the opposition and many locals, who feared clauses that allowed dual citizenship would dilute their voice in running the state, and drive up prices as rich Armenians from abroad, now allowed to keep their original citizenship would buy up the remaining resources and land, muscling out locals. The fear was not unfounded as rich Armenians from abroad made clear, one even offering to buy the State Museum of History and its priceless treasures.

The election was seen as a test of Armenia's maturity in democracy, and almost unanimously decried as fraud and a failure. The government refused to allow opposition to broadcast on state owned TV or radio, and violently opposed some demonstrations, While polling stations sat empty, the government still declared that two-thirds of the population had voted, 93% supporting the referendum.

Armenia Now

Much of the news in the past decade has been disheartening. A once proud, rich, literate republic is increasingly seen as a third world country bent on self-destruction. But there are still signs of hope and the legendary hospitality to foreigners that marked this republic in the past continue to make it a worthy destination.

Considered to have one of the most liberal investment climate of all the republics of the Soviet Union, more and more foreign companies are beginning to invest in Armenia's intellectual potential, with tourism and high technology leading near-future economic growth. This is further fueled by continuing remittances by Armenians living in Diaspora, to the tune of 300+ million dollars a month, or 3.6 billion dollars annually. Compare this to the annual budget of Los Angeles of $16.5 billion.

The difficulties facing Armenia are many, and it is with fortitude and terribly sacrifice that Armenians have just begun to climb out of their abyss. The collapse of the old economy has proved be have its blessings--if bitter and hard to bear. A privatization program and an austerity economic program agreed to with the World Bank is beginning to show signs of positive effect, though it neglects the elderly and disabled. A deepening of the capitalist system has created new opportunities for business, while the divide between the rich and poor grows large. Without state recourse for support, the population has begun to create a private sector that has transformed the face of Yerevan in the last 5 years.

The reopening of the Metsamor Atomic power station and supplies of natural gas from Turkmenistan and Iran restored electric power to the population, and the opening of land routes through Georgia is securing that growth. The government alternates between actively supporting investment in the economy and gouging potential investors for bribes, but the economy continues to hold to a small but steady pattern of growth.

A shrinking population

The government trumpets annual statistics showing steady growth, and its relative surge compared to other members of the CIS, but that needs to be tempered with the fact that current growth of as much as 7% is based on an extremely low baseline, and Armenia has yet to reach the level of productivity and income it had in 1989, the last year of reliable statistics for the Soviet Union. It is growth based on negative growth.

Life is very hard by western standards, with the majority of citizens living below the poverty level. Official statistics from the world bank (which cannot be taken as totally reliable) show that in the last 3 years the poverty level dropped from 59% to 50.9 % of the population, still a majority. Officially, the government admits to a drop in total population during 1989-2001 from 3.4 million to 2.4 million. This cannot be reconciled with airport and immigration figures showing a much larger drop. The most reliable figures are from business interests, which base their marketing decisions on hard figures and brutal facts: how many buyers are there for their products? They show a population of at best 2 million. A lower figure has been found at the government census bureau itself of only 1.7 million.

Figures provided by the Russian census bureau show a rise in the Armenian population to around 3 million throughout Russia, with 1 million in Moscow. This would make it a rival with Los Angeles for the most populated Armenian area outside of Armenia.

Armenians in Yerevan enjoy a better standard of living, and the city center seems under permanent construction and renovation, with ostentatious displays of wealth. There are over 1000 registered cafes in the center of Yerevan, many reinventing the idea of cafe, substantially built with fountains, gardens and permanent summer houses. Construction is rampant also in Yerevan center, new apartment (read "condo" in he US) buildings rising on most blocks, and the city streets undergoing significant repairs under a grant by billionaire Kirk Kirkorian (US Armenian who owns MGM). There are concerted efforts to attract tourism, and new hotels and restaurants also are appearing.

The rest of the country is poorer, but food and housing are seemingly provided for. There are reports of the malnourished, especially among the elderly, but starvation is unheard of and Armenia continues to be the most literate country in the CIS, despite the fact that education has seen a sharp drop in quality and access, with teachers leaving for more lucrative jobs elsewhere. Private tutoring has become the norm for those who can afford it, and investment in this sector is drastically needed if an irreversible slide is to be avoided. Medical care and care for the elderly are other equally pressing problems facing the country.

Assistance to the country comes in many ways: The UN, USAID, France, Germany and many other countries have a variety of programs, ranging from food assistance to macro-economic development. Considered a joke among most local Armenians is the assistance provided by most Diaspora Armenians, who just can't seem to bring themselves to actually help. A popular joke in the country is about the Armenian from Los Angeles who decided to help his cousins in Armenia by sending a computer. So he sent three parts to the computer that cost him about $50, and a list of parts his cousins would have to buy which cost about $500. None of his cousins knew how to use a computer, of course.

Armenians still value family above all else, and to make do with what they have. A small but persistent middle class has begun to make itself permanent, and continued focus on freeing the economy is making dividends in increased investment in the country. The events of the last decade are considered an anomaly in an anomalous land. But so is the entire history of Armenia.

At the same time, wealthy individuals from the Diaspora such as Kirk Kirkorian (of the MGM Grand fame) established programs that seem to work by holding the local leaders accountable for their work: For the first time in decades Armenia has a drivable highway linking Georgia and Iran, the Sevan Pass has been cleared and paved for truck traffic, major streets, sidewalks and Republic Square have been rebuilt, and a substantial program to renovate major cultural institutions in Yerevan and Giumri began.

By 2004, we can report there is continuing construction and ostentation in Yerevan, showing some kind of economic growth. The middle class continues to be workers at NGO and governmental institutions, with entrepreneurs either poor or rich , there seems to be no middle ground.

The regions are still poor to desperately poor, with farmers the only economic generators.

Politically, pessimism and cynicism has bread a kind of comfort, where change is seen as a threat (it is better to know the fox in your house than not the one outside your door), and people have given up on expecting real change for this generation, instead focussing on making ends meet.

Tourism continues to grow, the most positive indicator being last years figures of roughly 200,000 individuals. It is still considered the best chance to change the country for the better, as service jobs, income and new ideas flow into the country.

Top

Top

|