|

|

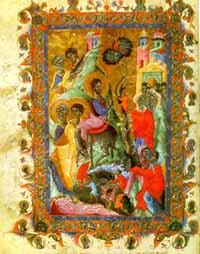

The

Entry into Jerusalem, Lectionary

1286, Cilicia

Exact origin, name of scribe and illuminator unknown

|

|

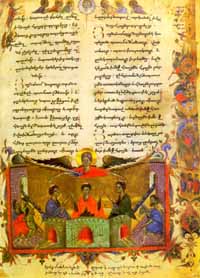

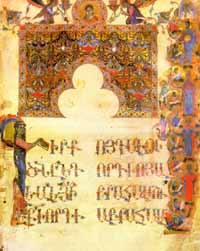

The

Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace, Lectionary

1286, Cilicia

Exact origin, name of scribe and illuminator unknown

|

The middle of

the thirteenth century marks the beginning of new creative searches

by the Cilician miniature painters whose achievements at this

time anticipate the forms developed by Byzantine art during the

Third Golden Age.

Cilician artists

of this period sought to break the constraints of medieval canons,

to impart spatial depth to their pictures and to achieve volume

and perspective in figural representation. The trend towards

a realistic depiction of traditional scenes was fully developed

by Toros Roslin.

Unfortunately, just

as with the majority of painters of this time, we know very

little about Roslin's life. According to the colophons of his

manuscripts, he worked at Hromkla between 1250 and 1270 and

was evidently the chief artist of the Patriarch's scriptorium.

He must have been quite a celebrity, for he received commissions

from the capital - from members of the royal family and courtiers.

His popularity was undoubtedly also due to the patronage of

the Catolicos Constantine I, one of the most educated persons

in Cilicia.

One of the most remarkable

manuscripts in the Matenadaran collection signed by Roslin is

the so-called Malatian Gospels (after the town of Malatia) of

1268 (Ms. 10675). It is one of the last, and probably the best

of Roslin's works. It was commissioned by the Catolicos Constantine

I as a gift for Prince Hetoum, son of Leon III.

The art of Toros

Roslin is both serene and magnificent; it combines quiet joyfulness

with light melancholy. The elegant proportions of the figures,

the strictly balanced composition, the ingenuity and variety

of ornamentation, the impeccable taste and moderation in everything

- in the colouring, decoration and choice of motifs inspired

by real life - betray a genuinely classical master of a calibre

which throughout the history of art is only found at the highest

peaks of its development.

The art of Toros

Roslin and of artists belonging to the same generation represented

the classical period in the development of Cilician book illumination.

The ensuing period which began some ten or fifteen years after

the last known work by Roslin was marked by considerable changes

in aesthetic principles, caused by changes in political and

social life. The two last decades of the thirteenth century

were also the end of the Golden Age of Cilicia, followed by

a slow but steady decline. The increasingly frequent raids by

the Egyptian Mamelukes (who in 1292 captured and plundered the

monastery of Hromkla) created an atmosphere of alarm and apprehension

in the country, which could not but tell on the art of this

period.

Following Roslin, the artists of the 1280s

introduce many details prompted by real life into canonical

schemes; like their great predecessor, they seek to convey

the feelings of their characters. But they "out-Roslin Roslin",

as it were, in their pursuit of the true-to-life, and sometimes,

in fact, distort the noble and lofty ideal created by him.

The faces in the miniatures of this period are often crude,

the figures elongated to the point of deformity, particularly

if compared with the almost Hellenistic proportions of Toros

Roslin's figures.

At the same time, their realistic depictions

bring a dynamic and dramatic effect to the miniature, something

Roslinís carefully crafted work sacrificed to achieve a lofty

and otherworldliness to his paintings. These are accessible

scenes from the bible, filled with the horror, joy and human

frailties of life.

|

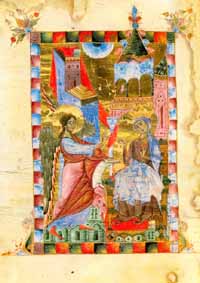

The

Annunciation, The Gospels

1287, Akhner Monastery

Written by Hovhannes, name if illuminator unknown

|

|

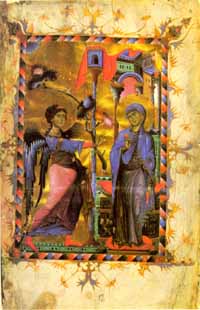

The

Annunciation, The Gospels

Ca. 1280

Origin, names of scribe and illuminator unknown

|

|

First page of the Gospel of St. Mathew

Ca. 1280

Origin, names of scribe and illuminator unknown

|

The group of manuscripts, which includes the Lectionary of

1286 (Ms. 979), is represented in the Matenadaran by another

example - the Gospels (Ms. 197) written in 1287 at Akhner

by Bishop Hovhannes, brother of King Hetoum I.

The Matenadaran

collection includes another Gospel manuscript dating from

approximately the same period (Ms. 9422). The highly expressive

character of this miniature is marked by it richly hued coloring.

A wide range of pastel tints supports the combination of red,

blue and gold, so typical of Cilician illumination.

The

luxuriously embellished headpieces that mark the Cilician

tradition is apparent in this sample from the 1280 Gospels.

The

original colophon for the 1280 Gospels is unfortunately lost,

but a later, fourteenth-century one survives and presents

a dramatic record of the various mishaps that befell the book

in the monastery of St. John the Forerunner in the town of

Mush (Western Armenia).

In

the middle of the fourteenth century the monks had to hide

their most valuable manuscripts, including the Gospels in

question, to save them from the invaders. When, many years

later, the manuscripts were removed from their secret hiding-place,

it turned out that many of them "had rotten away and were

impossible to read". The monks buried the damaged books, but

fortunately this became known to a certain deacon, Simeon,

who gave orders to have them dug up and hired an expert to

restore them. After restoration the books were returned to

the monastery. Surprisingly enough, the Cilician Gospels which

was among those manuscripts still retains a remarkable freshness

of paint and much of the brilliancy of its rich iridescent

colors.

Another outstanding

Cilician manuscript in the Matenadaran collection is the Gospels

traditionally referred to as the "Gospels by Eight Masters"21

(Ms. 7651).

The character of

its illumination differs from the traditional Armenian book

painting, particularly with regard to the arrangement of illustrations

and ornaments. There are no full-page miniatures; they are

incorporated into the text, forming frieze-like bands - a

method rarely used by Armenian painters and in this case evidently

due to Byzantine influence.

The manuscript

was written in the late thirteenth century by the celebrated

Cilician calligrapher Avetis who apparently worked in the

city of Sis. It was then turned over to a team of painters

for illumination, though for some reason or other the work

was not completed. The subsequent history of the Gospels is

known thanks to a colophon left by its second owner - Stepanos,

bishop of Sebastia - who received the book as a gift from

King Oshin.

The colophon reads:

"I, the worthless Stepanos, bishop of the town of Sebastia,

a lost shepherd and the poor author [of these notes] set forth

to the God-protected country of Cilicia on a pilgrimage to

the relics of St. Gregory. There I met with an honorable reception

and respect from the Patriarch Constantine and King Oshin.

And the devout King Oshin wished to honor me, the worthless

one, with a gift, and I, refusing all things vain, expressed

the wish to possess a book of Gospels.

And on the King's

orders I entered the palace treasury where the holy books

were kept, and when I saw them my heart rejoiced at this book,

which was written in a beautiful cursive hand and adorned

with many-colored pictures, but which was not complete in

its illustration, with some pictures merely outlined, and

still more entirely blank.

|

Christ

brought before Caiaphas, The Gospels

1320, Cilicia

Written by Avetis and Stepanos, illuminated by eight

artists, Sarkis Pidzak among them

|

And take the manuscript

I did, with great joy, and started to search for a skilful

artist, and found a devout clergyman Sargis, called Pidzak,

who was experienced in art. And I gave him 1300 drachmae of

my righteous earnings, and he undertook to complete the unfinished

pictures and decorate them with gilding, which he did with

great skill and care, and I, having received the completed

manuscript, rejoiced in my heart. And all this came to pass

in the year 769 [1320] by the Armenian calendar, at a time

of trouble, evil and misfortunes of which I find it unnecessary

to write ... "

Sarkis Pidzak was

the last prominent figure in Cilician book painting. In 1375

Sis, the capital of Cilicia, fell to the armies of the Sultan

of Egypt, which meant the end of Cilician Armenia and, consequently,

the end of Cilician Armenian culture.

|