|

| "In

the Metsamor kingdom, early script forms go back to around

2000 BC " |

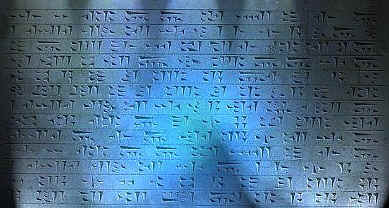

When Sumeria perfected the wedge-shaped cuneiform around 3000

BC, it introduced an alphabet to the world, and the relatively

quick and easy method of describing things (and oh how the Sumerians

loved to describe things 80% of their clay tablets are lists

of things) caught on with other countries.

While it influenced

other attempts at writing, it did not usurp them. In the Metsamor

kingdom, early script forms go back to around 2000 BC. The

script uncovered in this period has moved away from simple iconography

to symbols with complex meanings, and they appear in lines or

groups the first sentences created by ancestral Armenians. The

symbols are very far removed from Sumerian wedge shaped slashes

on clay they function as a communication device while at the

same time they are elegant pictures of divine presence on earth.

Accomplished astronomers

a thousand years before the Sumerian Script, ancestral Armenians

were steeped in a religious iconography revolving around the

sun, the moon, the planets and the stars. A pantheon of gods

inhabiting the constellations of the zodiac which experts believe

had been completed ca. 2800 BC was "captured" in sacred script

found at places of worship. By around 2000 BC, the "Metsamor

Script" had been codified and was widely used in ancestral Armenian

lands. Not so curiously, this script is found outside urban

areas, and appears in remote areas of the country places where

it is easy on a clear night to gaze at the stars and identify

the home of the gods, to catch their moods and predict future

events.

As

a script reserved for religious purposes, writing and divining

symbolic meanings were reserved for the priest classes and here

is something scholars neglect to inform readers in their thesis’.

The fact you can read this article at all is a miracle of the

modern age. The vast majority of the population back then could

never have deciphered their script, even if they had been allowed

to read. They were illiterate. As

a script reserved for religious purposes, writing and divining

symbolic meanings were reserved for the priest classes and here

is something scholars neglect to inform readers in their thesis’.

The fact you can read this article at all is a miracle of the

modern age. The vast majority of the population back then could

never have deciphered their script, even if they had been allowed

to read. They were illiterate.

Regardless of the

intricacy, beauty or functionality of any old script from the

majestic Egyptian Hieroglyphs to the compact Sumerian cuneiform,

or the elaborate Chinese pictograms writing was reserved for

the upper classes it was a weapon as strong as any sword in

keeping the peasants passive. Literacy is a recent event in

the concept of time it isn’t widespread in the "civilized" countries

until the end of the 19th century, and is only now

making inroads worldwide.

To a great extent,

the picture quality of old scripts was kept even as a culture

moved to more efficient ways of writing, simply to give the

peasant class some clue as to what the authors were up to. While

they could never have understood the intricacies of pluperfect

or passive tenses, let alone the grave error of a dangling participle,

they could spot a spiraling sun disc placed over the

head of the king. They lived in pictures, studied them for spiritual

meanings, and were comforted or terrorized by the interpretations

made by the priests.

Writing was kept

by the religious class, and passed on to only a select few.

Sometimes the aristocracy could read, but there were more than

a few kings who didn’t have a clue what their own priests were

writing. I like to imagine the development of reading had a

lot to do with keeping tabs on what the scribes and priests

were up to, as much as it did with impressing the locals with

erudite learning. By the time Urartu rose, second sons were

routinely assigned positions of High Priest, keeping the family

business of running an empire close at home. Wouldn’t want anyone

changing the archives just when we are about to enter eternal

god-status, now would we?

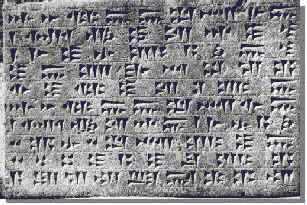

By the time Urartu

rose in prominence in the region, they had developed a dual

system of writing. Visitors to Urartian excavations like Erebuni

learn that Urartu used cuneiform, and that it was borrowed from

Assyrian script.

For

a while this caused classical scholars to surmise that Urartu

was little more than a regional power that absorbed a more refined

Assyrian culture as they rose to power. And it seems to fit:

A mountainous tribe captures most of Anatolia and then looks

up from the dust to find a glorious culture to the South. To

read some scholars, the ensuing wholesale "invasion" of Assyrian

architecture, design and religious iconography reads like a

country cousin rampaging through Rodeo Drive on credit. ("Like

that Babylonian bull effigy, Marj? We’ll take fifteen hundred

for the temple. Oh, and throw in a few hundred lapis lazuli

snake charms for the mid-winter banquet."). Oh, those classical

scholars. For

a while this caused classical scholars to surmise that Urartu

was little more than a regional power that absorbed a more refined

Assyrian culture as they rose to power. And it seems to fit:

A mountainous tribe captures most of Anatolia and then looks

up from the dust to find a glorious culture to the South. To

read some scholars, the ensuing wholesale "invasion" of Assyrian

architecture, design and religious iconography reads like a

country cousin rampaging through Rodeo Drive on credit. ("Like

that Babylonian bull effigy, Marj? We’ll take fifteen hundred

for the temple. Oh, and throw in a few hundred lapis lazuli

snake charms for the mid-winter banquet."). Oh, those classical

scholars.

Thankfully, new

information has come to light showing there was as much influence

on Assyria by the Urartians as vice versa. While the Assyrians

seem to have taken Sumerian and Babylonian worship of animal-gods

and sent them north to Urartu, the entire Assyrian astronomical

tradition can be traced to the much earlier Metsamor period.

Almost identical designs used in Assyrian frescoes and carvings

have their earliest representations in the Armenian plateau.

As for script, the

Urartians placed cuneiform in public places, designed to assert

authority over anyone who could read it which would have been

one of several thousand Assyrian prisoners taken in battle.

The educated prisoners understood the meaning of the use of

"their" script: A power had risen in the North to rival their

own, great enough to absorb the culture of the South. Most depressing

of all, it was great enough to change it to a more refined style.

Frescoes uncovered in Assyrian palaces and throne rooms from

the period show whole scale adoption of Urartian symbols and

designs.

For the other, illiterate prisoners, it was a blow against myths

that Urartu was nothing more than a bunch of mountain tribes.

Not only did they copy the sacred Assyrian script, they flung

it in the face of their enemies.

For the other, illiterate prisoners, it was a blow against myths

that Urartu was nothing more than a bunch of mountain tribes.

Not only did they copy the sacred Assyrian script, they flung

it in the face of their enemies.

And Urartians used

a second script along with cuneiform. This script seems to be

reserved for more prosaic uses, though symbols appear along

with cuneiform in temple and palace areas. The Urartian script

is a much-developed version of the Metsamor Script, though it

still relies on pictures to communicate ideas. Rival Haikasian

script had begun the conversion of pictures into more abstract

symbols. Whether either were used like alphabets to capture

sounds that are strung together to make words no one who wasn’t

around at that time really knows.

During the Urartian

period (ca. 1200-650 BC), other scripts were used in ancestral

Armenia, among them the Armavir (1100 BC) and the Cholagerd

(850-750 BC) scripts.

Neither script has

been found to include more than a few symbols, and none have

been deciphered adequately to tell whether they were actual

words, pictures of events, or geographical map symbols. They

seem at first glance to be holdovers of the earliest pictogram

tradition in the area, and since they were used by remote tribes,

they might represent a sort of local dialect.

|